Touring a World of Story Structures

Part 1: Kishōtenketsu

I won’t lie. This came about because of the last post I made about slice-of-life as a genre of fiction. After my post, I became interested in learning more because slice-of-life didn’t quite fit the same narrative structure that we are consistently taught (at least here in America). So, I went down the rabbit hole and learned there was so much I needed to learn.

And… so much is not easily available. When one searches bookstore websites for story structure books (maybe I should have been searching storytelling instead of story structures, but that’s a different story), it didn’t feel like there was much which enveloped the whole world. I felt like it was far easier to find things like Save the Cat and Romancing the Genre which utilizes the three-act structure and conflict.

For the purposes of this article, I’m using online resources, but as this is a topic I’m hoping to bring to a convention as a panel discussion, I’m looking into journal articles and books as well. This is serving as a reason to deep dive into this research more for my own purposes and fascination and my articles may need to change over time as I continue my research.

More than three acts

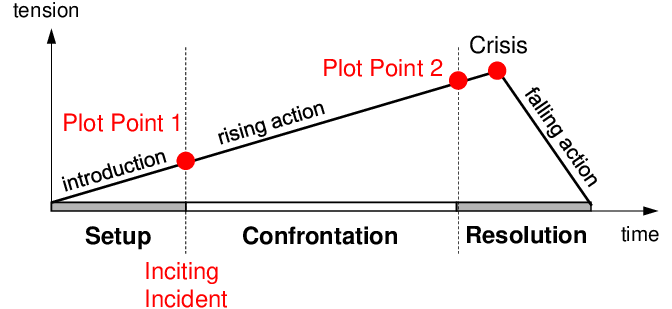

What I didn’t know, and what we are generally taught in American schools, is that the three-act story structure found in most films and novels potentially originated from Syd Field. I guess that this was previously attributed to Aristotle, but apparently, Aristotle prefers the two-act structure instead (essentially a “complication” and “denouement”).

Even my oldest son, who is now entering 5th grade, learned this story structure in 4th grade.

This structure is so familiar and so overtaught that many American authors probably rarely think there are other options out there. But when talking about slice-of-life and what we in the West call the ‘cozy genre,’ there is very little crisis or conflict—so little, in fact, that this doesn’t quite describe it properly. Because, at the end of the day, there wasn’t a crisis or rising conflict but more of a subtle twist of events and then a close.

Stories can be considered a reflection of cultural values. For the West, including Western Europe and America, individualism is valued and can lead to economic success. Conversely, collectivism is how societies in Eastern Asia (China, Korea, Japan, and so on) thrived, where conformity and societal harmony are placed at a higher value than individual uniqueness.

Conflict is the central theme within the three-act structure. Without conflict and (eventually) a resolution, the story can feel incomplete to Western audiences. This would be the crisis in the chart above—something that must be overcome by an individual.

I particularly love this quote from this blooloop article about “Storytelling & Culture: East Meets West part 1”: “Collectively, Westerners have a romanticized perception of the individual’s ability to overcome any obstacle. Regardless of how insurmountable it may seem. They want to imagine that with enough grit, tenacity, determination and even a little luck that any challenge can be triumphed.”

Many categories of stories, like The Hero’s Journey, may have many more points (classically, Campbell’s Hero’s Journey is 17 points) but are still grouped within the three-act structure.

Kishōtenketsu - Four Acts, less conflict

So, what are some other story structures? There are such a vast array, clearly this series can go on for a while. But, considering this all started with that last article on slice-of-life, let’s start with my foray into Japanese storytelling structures since that’s where I started my research.

Kishōtenketsu originated in China under 起承转合 qǐ chéng zhuǎn hé, but Japan, Korea, and China’s structures each differed slightly as they evolved. Again, considering this started because of my recent anime watches and manga reads, I will focus on the Japanese structure of kishōtenketsu.

The structure of kishōtenketsu may not feel all that different at first by adding one more act.

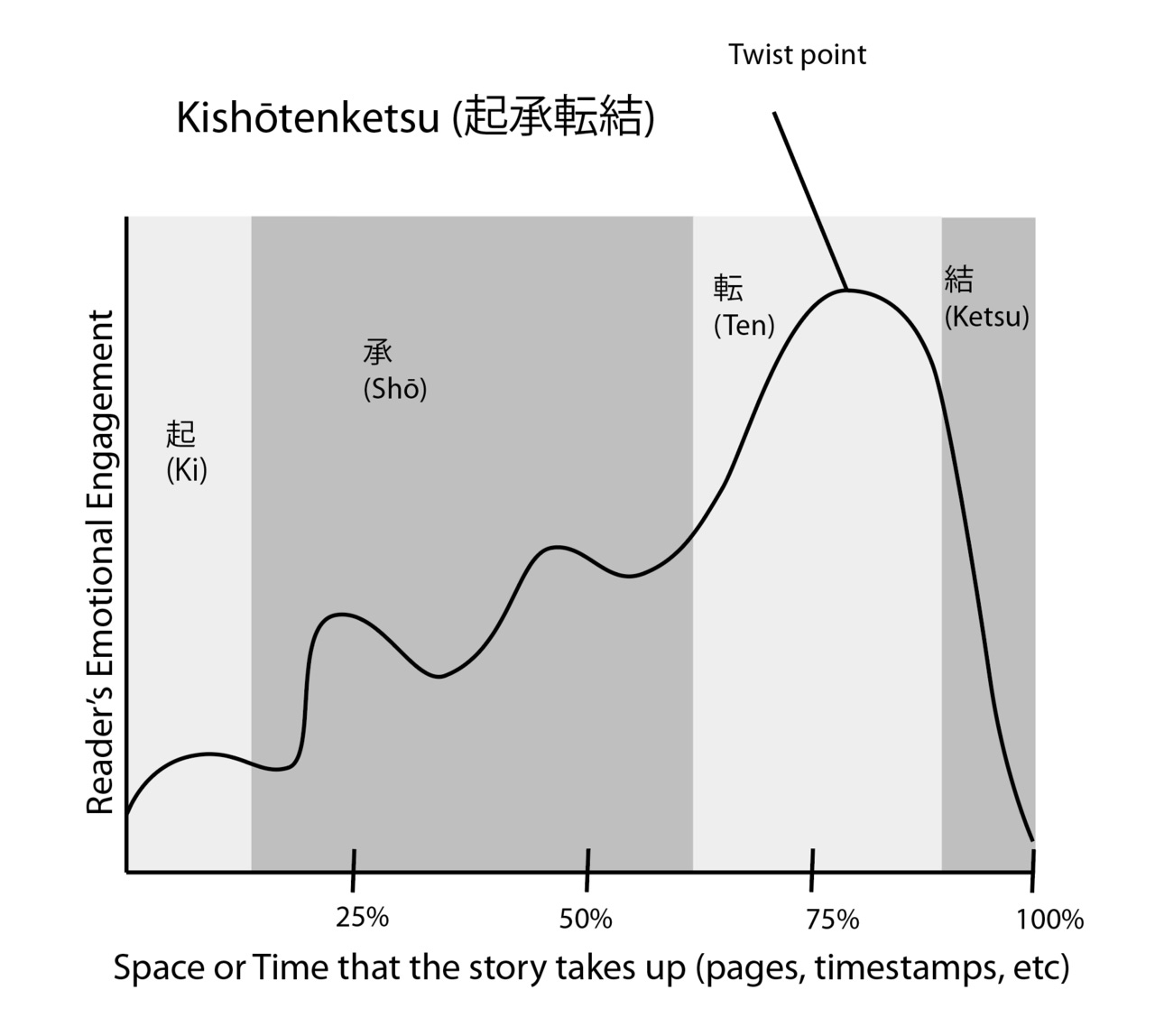

A note: While I have not discussed with the author of this incredible article, Worldwide Story Structures, directly, Kim Yoonmi has discussed with other authors the importance of hiring one's own voices or people with lived experiences. I’m not in a position to that for my free blog for it’s graphics or even writing this article, but I absolutely agree. For me, this is me sharing what knowledge I have found, but also linking the sources I am finding these articles in. Please go support these voices and hear what they have to say. I also hope I’m linking to the original source, and I will make updates as needed if I have not. I would like to show the most accurate depiction of the 4 act kishōtenketsu structure. Above is Kim Yoonmi’s depiction, which is linked to her article. She has also suggested this video, which greatly describes the structure, likely in better detail than I will ever give.

As the title of this section suggests, there are four acts to this structure, which are as follows (from the Wikipedia page):

kiku (起句) is 'ki (起)': introduction, where 起 can mean rouse, wake up, get up

shōku (承句) is 'sho (承)': development, where 承 can also mean acquiesce, hear, listen to, be informed, receive

tenku (転句) is 'ten (転)': twist, where 転 can mean revolve, turn around, change

kekku (結句) is 'ketsu (結)': conclusion, though 結 can also mean result, consequence, outcome, effect, coming to fruition, bearing fruit, etc.

Where a Western story may introduce a conflict early on (in a recent workshop at my writer’s group, it was suggested a conflict must be introduced in the first chapter), kishōtenketsu will rely heavily on setup and development before the high point of the story, ten (or twist).

A point Kim Yoonmi brings up that I found particularly interesting is that kishōtenketsu is heavily based on self-realization, -actualization, and -development. While the changes to a character may not be huge, a small change (be it good or bad) is necessary over the course of the character’s arc. This is exactly a point seen in many slice-of-life anime.

Let me use a recent example I read/watched. SPOILERS ahead for the anime/light novel/manga of The Apothecary Diaries.

In the second half of the season/second light novel, Maomao and Jinshi are at odds with an odd military tactician, Lakan, who is introduced at the beginning of the second cour (introduction or ki). It is discovered relatively early on that Lakan is Maomao’s biological father. We find through interactions primarily between Jinshi and Lakan (but also others, like at the Verdigris House and on the palace grounds) that Lakan knows the Verdigris House well, and he even enraptures Jinshi with a story about a woman he loved there. The story of Lakan develops as he helps Maomao save Jinshi and she then finally decides to meet him face to face and play his favored game (still well within the sho section of the structure). Tensions do rise during this game, as Maomao does make a bet with Lakan, and I would argue the twist (ten) in this case may be when she wins the bet by making Lakan so drunk with one drink that he passes out. The ketsu, or consequence, is that he must fulfill the bet, which is to purchase out one of the girl’s contracts at the Verdigris House. However, Maomao knew that her biological mother was still there and alive, albeit very sick. Lakan’s story ends (thus far as I have come across) with him learning she is still alive and choosing to purchase out her contract and be with her for her remaining days. This circles around to what Lakan had wanted to do so many years before but had been unable to do.

In this entire arc, there wasn’t a conflict in the sense we would see in Western-style stories. Tension and conflict are not one and the same here.

A difference to note is that the resolution to kishōtenketsu can be open-ended. The conclusion is a conclusion to the twist, not necessarily everything wrapping up and having an absolute end.

I found the example in this article from Art of the Narrative interesting. The author utilized an urban legend as an example and noted that the characters don’t need to show growth, have goals, or overcome a conflict.

Wait, if there’s no conflict… what happens at the end?

Well, that might depend on your character. One possibility is that life just continues on. The urban legend mentioned in the Art of the Narrative article shows that life just keeps going on. Something weird happened, and the characters didn’t really learn anything; it was just a weird event in their lives.

It reminds me of the story Calypso tells Bluey’s class in the recent long episode, The Sign. The story goes something like this: A farmer has a horse who runs away, and the townspeople tell the farmer what bad luck that is. But the next day, the horse returns with several wild horses, and the townspeople say what good luck that is. Then, the next day, the farmer’s son tries to tame one of the horses and is thrown off, getting hurt in the process. The townspeople decry it as bad luck. Then, the next day, the king orders all the sons of the townspeople to enter the military, but the farmer’s son is injured and cannot go, which the townspeople say is good luck.

And that was where the story ended. It was quite open-ended, and while it ended on good luck, the message Calypso was trying to tell Bluey was that things work out as they are supposed to. Sometimes, it’s good, and sometimes, it's bad. This actually mimics how life goes, as well. Many times, there is not a solid conclusion to a story, just a resolution of a ‘twist’ or something that happened which can be a way a story using kishōtenketsu ends.

Is this a complete look and breakdown of the kishōtenketsu as a structure? No. But I think it’s a fascinating beginning and hope that like I got interested in looking at story structures beyond what we’re taught in school (at least here in America) that it inspires others to look into the same subject and broaden your horizons. The linked articles are fascinating and definitely add more context, so please go read them as well. Please, please, please, listen to your own voices and lived experiences over mine. I want to share what I have learned, but I am no expert. I find this absolutely fascinating, and I hope that it inspires others as well.

Thanks for sharing; I have been in need to get perspective on different writing styles.